Have you ever looked at a photo and felt… struck? Your breath catches, a flash of emotion, there’s a visceral reaction you can’t quite put a finger on. You are affected, and you sit there staring at the photo trying to find out why, but you just can’t quite place it.

What is that?

I’ve been searching for it lately, and it’s brought up more questions than answers. Questions like what makes a photo great or meaningful? What is it about an image that can have such a physical effect on us?

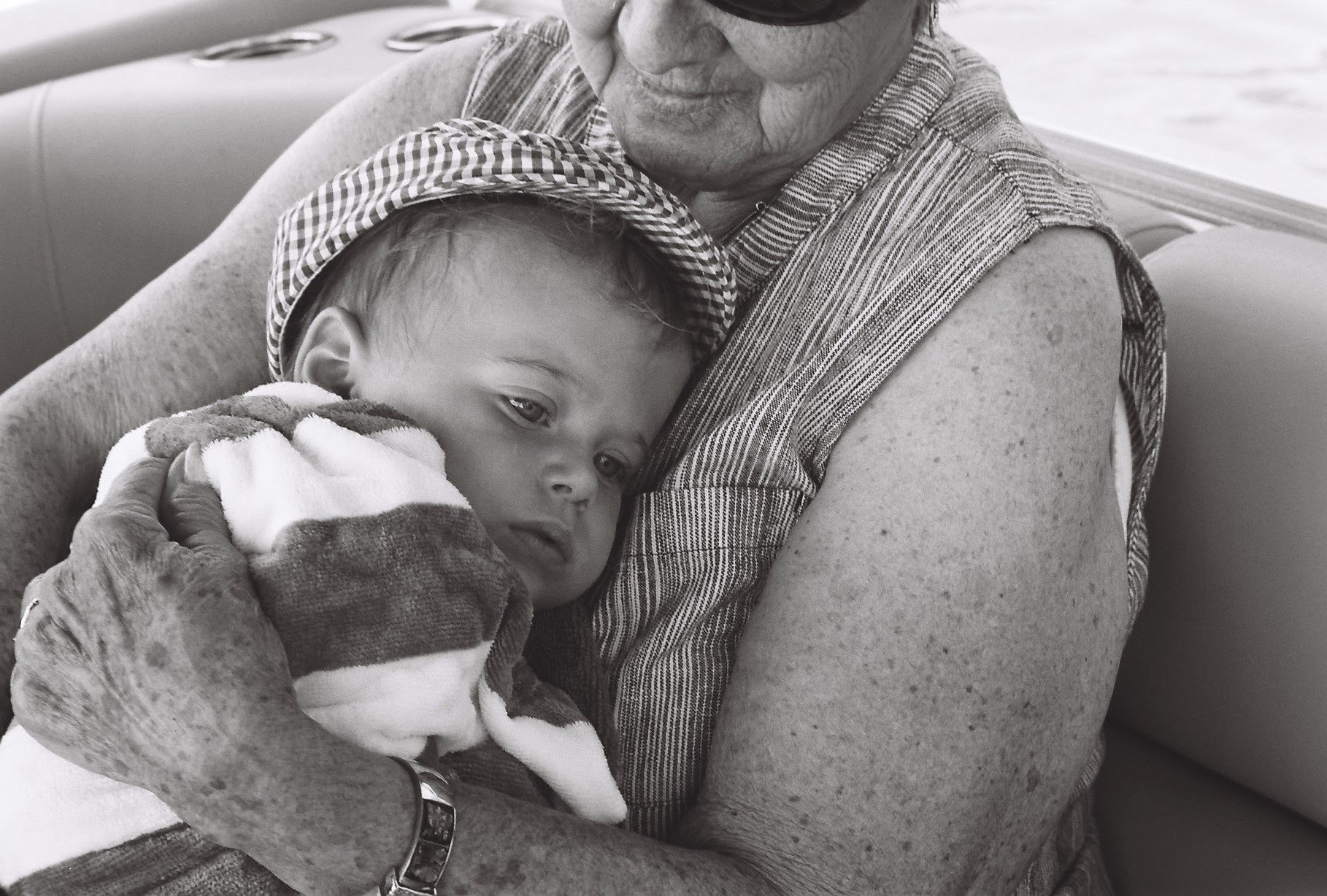

My search and the inspiration for it lies in one place, what I’ve been calling my personal documentary work—images of my family and friends, of myself, of the day-to-day, or photos from an important trip or place. Those photos matter the most to me, and have been the ones to give me that unplaceable feeling most often. But not every photo of these subjects achieves this, while images by other photographers have struck me even harder than my own.

So what is it, how do I find it, and most importantly, how do I make more photos like that?

To try and answer that key final question I had to back up to where it started, with Sally Mann’s Immediate Family.

Searching with Sally Mann

“The things that are close to you are the things you can photograph the best, and unless you photograph what you love you’re not going to make good art.”

Sally Mann, “What Remains” documentary

Published as a controversial photo book, the project documented Mann’s children as they grew up. It was controversial because of the raw depiction she used, sometimes nude, with scrapes and bruises, or posed with a cigarette in hand. Critics said the children looked almost feral. You can read more about the controversy here and here, but thats not what I’m focused on.

Immediate Family changed how I view the seemingly mundane act of documenting your day-to-day. There was something in the photos that grabbed me. It was emotion choking me, something screaming out to me that I couldn’t understand. That feeling. I don’t know Sally Mann or her children, but what I felt was more than just appreciation for a great photo.

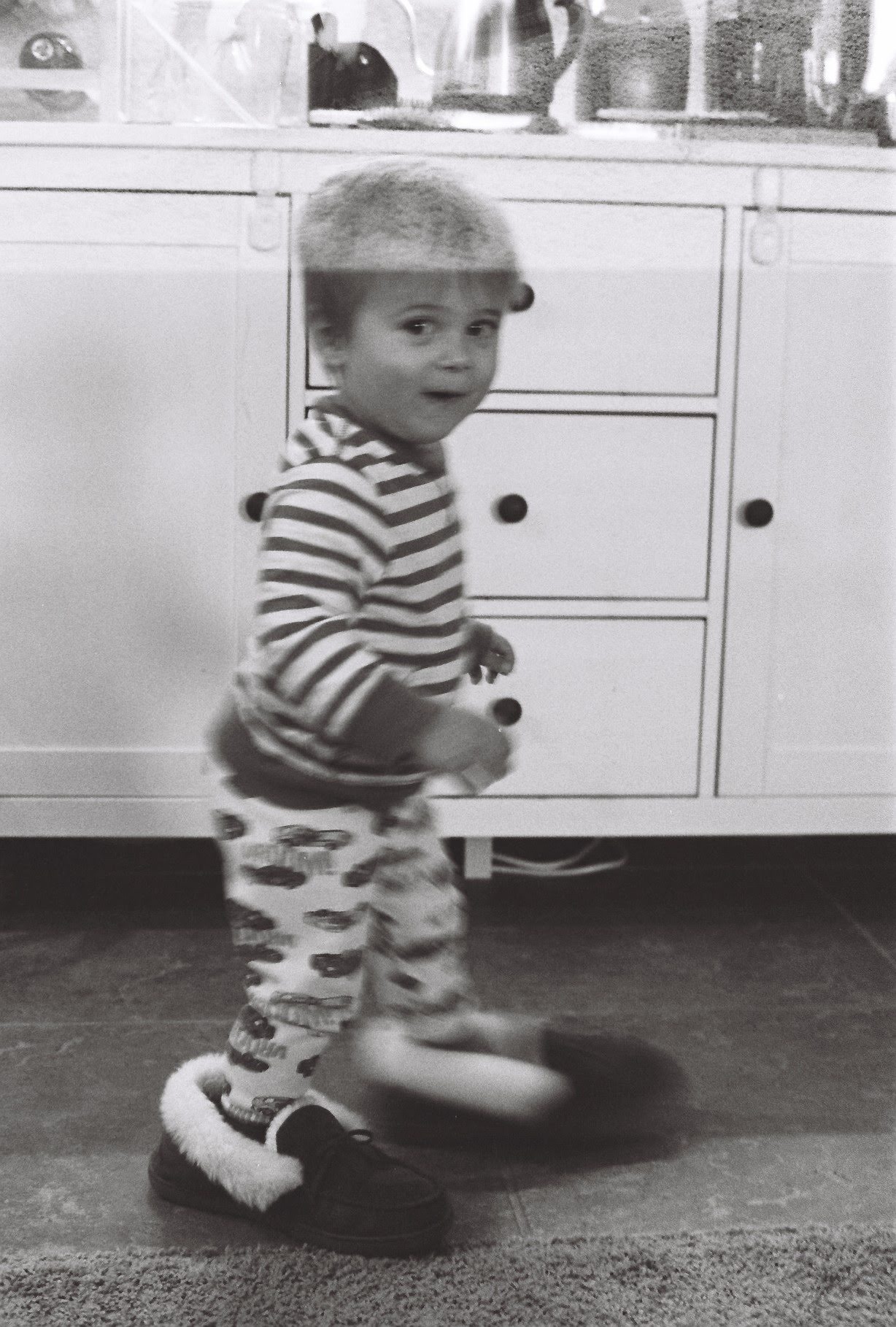

I started trying to emulate what I felt from Immediate Family in my own photos, initially by copying the medium as much as possible. I wasn’t shooting on 8×10 large format, which absolutely effects the quality and feel of photos. But I started shooting more personal work on black and white film, experimenting with different stocks to try and get the contrasty, soft, timeless look from Mann’s photos. Beyond the medium, I was struggling to place exactly what I was seeking to emulate in her photos. That feeling again. What was it?

Finding the punctum

“A photograph’s punctum is that accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me) … it is this element which rises from the scene, shoots out of it like an arrow, and pierces me.”

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida

I found my answer in Camera Lucida, the poignant book on photography by French literary theorist and philosopher Roland Barthes. Barthes described my feelings perfectly, and named the perpetrator the punctum. The punctum is opposite to what he named the studium, the factor that initially draws you to a photograph. The studium refers to the intention of the photographer, the elements of the image we can understand logically.

Barthes came to understand the punctum viewing the Winter Garden Photograph, an image of his mother he found after her death.

“There I was, alone in the apartment where she had died, looking at these pictures of my mother, one by one, under the lamp, gradually moving back in time with her, looking for the truth of the face I had loved. And I found it.”

The punctum is what makes a photo greater than the sum of its technical parts. For Barthes viewing the Winter Garden Photograph, it achieved “…the impossible science of the unique being.” This is exactly what I was feeling when I first saw Immediate Family. I see those kids in the images, even though I can’t name the feeling or what exactly is causing it.

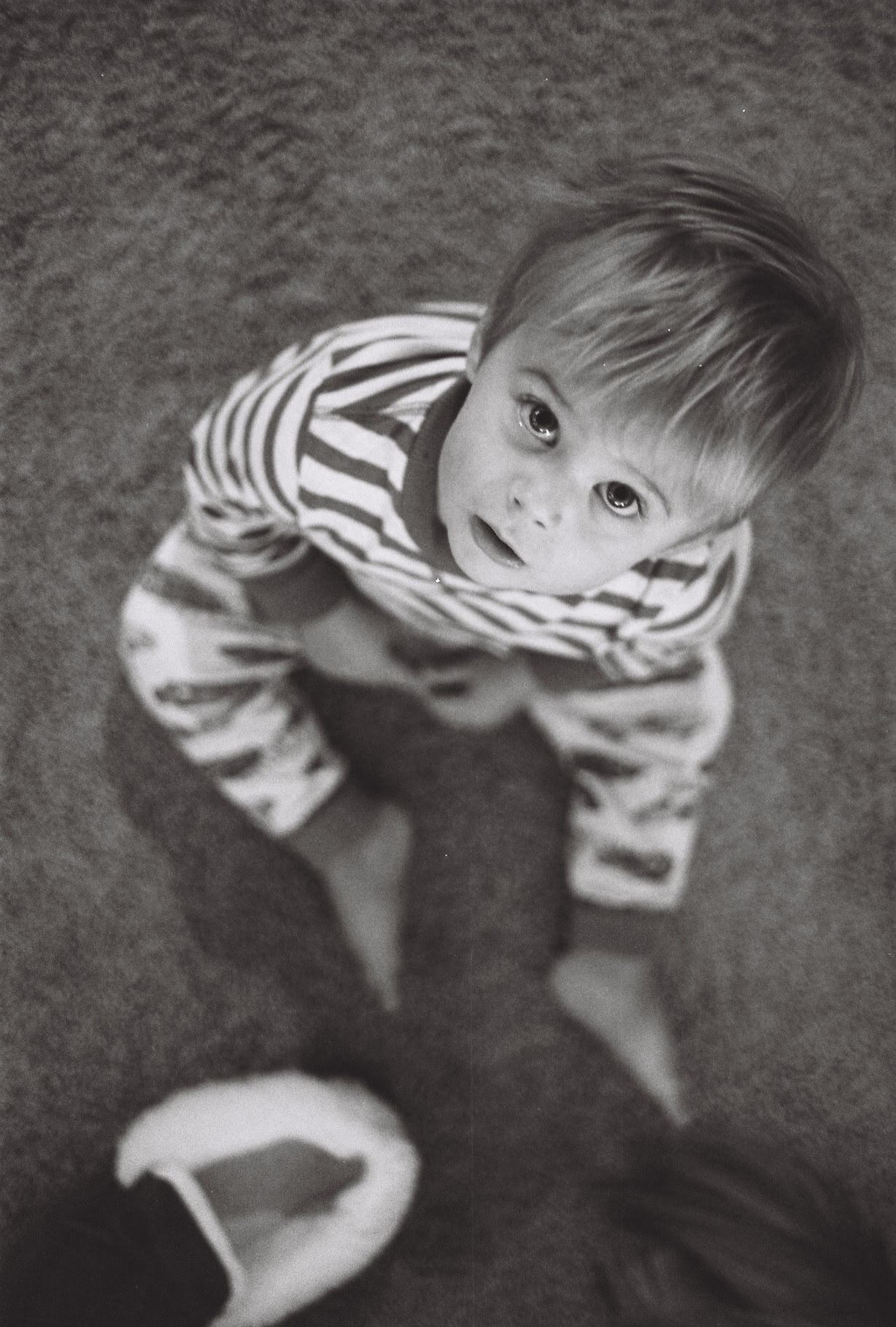

When I look at my work, especially what I’ve made since getting inspired by Mann, there’s one photo that stands out above all else to me. This photo of my niece, Lottie Rose.

I don’t remember taking this photo. I didn’t know it would be one of my favorites I’ve ever taken, but the first time I saw it my breath caught in my throat. I can’t explain it. Is it her expression, the small bags under her eyes that run in my family, the pose and confidence, the qualities of the photo itself? Yes, maybe? I studied this photo for over a year before I read Camera Lucida trying to figure out why I was so affected.

The photographer’s second sight

I had my name, now my search was for the way to do this again. I kept reading and Barthes had answers, just maybe not the ones I initially hoped for.

“What I can name cannot really prick me. The incapacity to name is a good symptom of disturbance.”

“The studium is ultimately always coded, the punctum is not.”

There’s the rub. The punctum cannot be named. It can’t be on purpose. If you’ve found the studium you’ve discovered the photographers intention. The photographer can’t intentionally create a punctum in an image.

At first this deflated me. I’m pragmatic, so telling me there’s no clear path to doing something frustrates me. But the more I read, the more Barthes explained the nature of the punctum.

- It’s personal. What strikes you may not strike me. It’s subjective to our inherent being. “…it is what I add to the photograph and what is nonetheless already there.”

- It changes over time. A photo that means nothing may knock you off your feet a year later. “In order to see a photograph well, it is best to look away or close your eyes.”

- It’s unpredictable.

While frustrating for a pragmatist, the unnameable nature of this actually opens up the possibilities of photography. This unknown, subjective pull we’re all searching for is what makes photography a lifelong pursuit.

According to Barthes, it’s also less restricted to professionals.

“Usually the amateur is defined as an immature state of the artist. Someone who cannot—or will not—achieve mastery of a profession. But in the field of photographic practice, it is the amateur, on the contrary, who is the assumption of the professional: for it is he who stands closer to the noeme of photography.”

Note: Phonetically, noeme means an irreducible unit of meaning. A.k.a. the core meaning. Barthes defines noeme as “that has been” in relation to photography.

How refreshing is that? No gatekeeping, no secret sauce that only the pros know, but a power available to any photographer today with a phone in their pocket. There is one final quote that brings it all together for me, a resting place to guide my pursuit of this idea.

“The photographer’s “second sight” does not consist in “seeing” but in being there.”

We can all make work that’s meaningful. We just have to be present and capture it. A simple answer with a lifetime of implication. Style, composition, medium, all can be copied and experimented with. They should be, it’s part of the fun. But they’re means to an end, an end that isn’t really an end but a lifetime of gathering moments that give you that unnameable feeling.

You’ll never know which photo will be the one that strikes your friend, your family, or you, but when it happens you’ll recognize it.

“I don’t know what it is, but it’s just her.”

Isn’t that a gift worth searching for.

Comments

Loved reading this, Alex. Philosophy around photography, art, and personal expression.