Looking back on our lives, it’s easy to see phases of varying lengths and intensity. Maybe its a human thing, we get really focused on something for awhile then move on to the next. Sometimes phases become identities. Sometimes identities are torn away, and sometimes they become who we are forever.

When the pandemic hit in earnest last spring I launched myself into a new phase, one of physical effort. I spent the summer of 2020 power-hiking and eventually jogging around the local Boulder trails, then continued scrambling in the San Juans and running in the Indian Peaks Wilderness. Life was simplified in a way I didn’t expect with most social activity and other hobbies shut down. Work, run, repeat.

As summer wound down, my friends Nate, Josiah, my pup Scout, and I escaped north to the Wind Rivers for what’s becoming a Labor Day weekend backpacking trip tradition (I wrote about the previous years trip here).

What followed over the next 5 days was what I like to call a perfect trip.

Our goal was Titcomb Basin, a popular zone 15 miles into the Winds that culminates at the Titcomb Lakes. The lakes sit at the western base of Fremont Peak, and are guarded to the north by multiple peaks and glaciers.

I’m an Indiana kid who found the mountains through the rockies in Colorado. My loyalty to these mountains runs deep. Nate, who has talked about this zone since I met him, was insistent about the epic scale of the Winds. I trust his opinion, but I was guarded, my heart locked tight.

Until it was torn open immediately and mercilessly. Don’t tell Colorado.

I knew I was in trouble at Photographer’s Point, an expansive viewpoint of the entire zone just five miles in. Fremont Peak is a granite behemoth shaped like the RCA Dome where I used to watch the Colts play growing up. Driving into downtown Indianapolis the white fiberglass roof would come into view bringing the familiar excitement of game day. The feeling is similar seeing Fremont stand watch over the entire basin.

The ten miles between Photographer’s Point and Fremont are a perfect example of how elevation changes the environment. Lush forests and small lakes slowly give way as the granite roars up from underneath, spilling out through the brush as you reach the alpine, replacing the trees and taking ground until the brush also succumbs to its unstoppable rise.

We spent a night by Seneca Lake, swimming until sunset before making base camp for a couple nights in an empty area northwest of Island Lake.

The next two days were spent chasing some of the most stunning sunrise and sunset photos I’ve ever taken, fishing around the lakes and various streams and pools between them, and relaxing in perfect weather. We had heard from folks on the trail that it snowed the day before we started the trip. Our final day on the way out smoke from the incessant wildfires that tore across the western US moved into the area casting a shroud over everything, reminding us of all the chaos that didn’t just stop at the trailhead. But for the five days we were there, perfection.

Yet I still found myself a bit restless. I was still in a phase, and a different one than Nate and Josiah. Nate wanted to fish non-stop, Josiah to write and relax taking in the views. All the while Fremont stared me down. I’d spent the whole summer pushing myself in the mountains, and the itch wouldn’t let me fully relax. The night before our final full day in the basin, we all chatted about going for the summit and noncommittally said we’d decide in the morning.

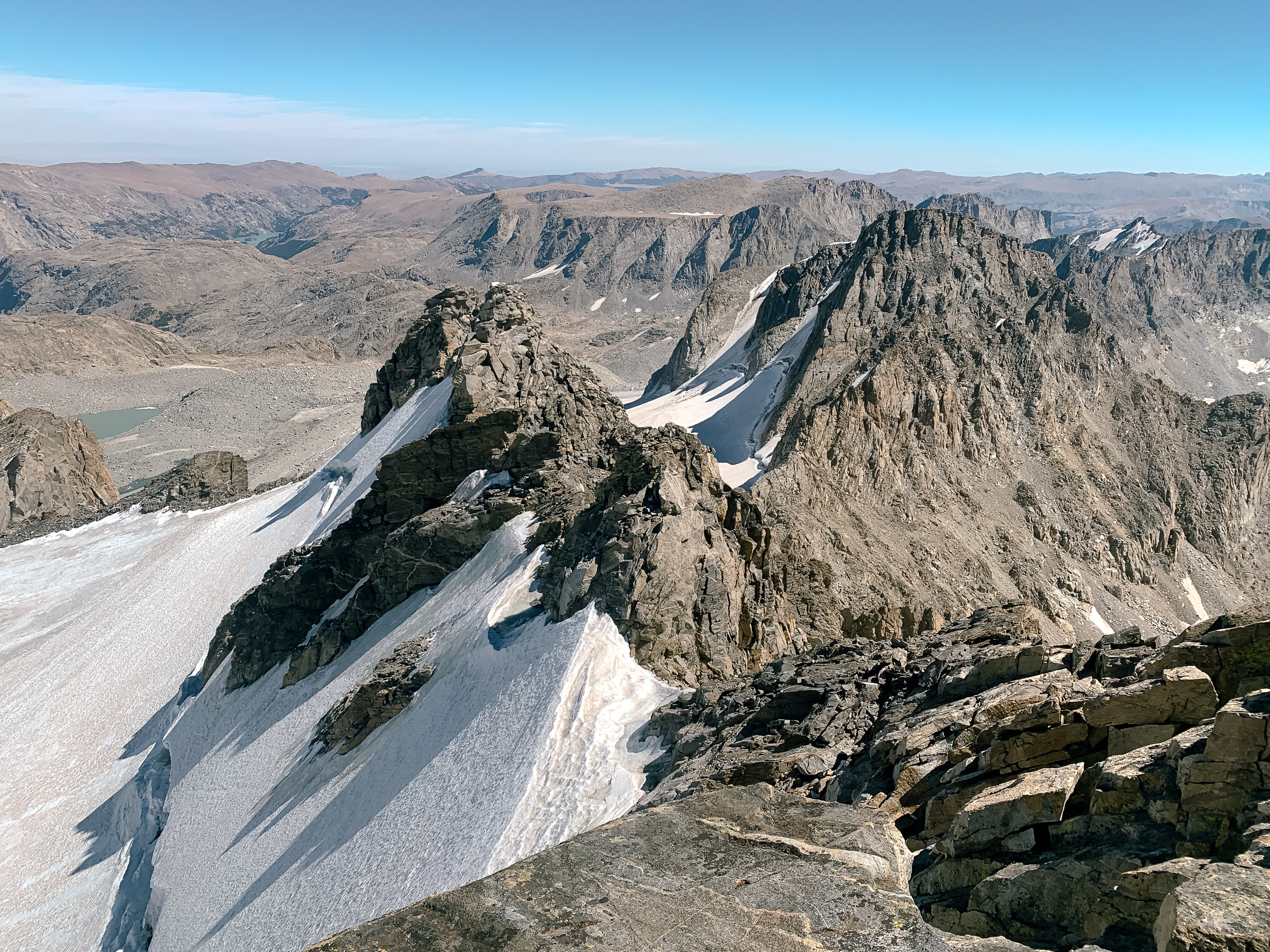

The next morning I took off from camp, solo, to summit Fremont Peak. While not very technical, the days with a heavy pack wore on me and made for a slog. The southern saddle provided a boost, with views of our entire journey so far. The summit itself was rocky, windy, exposed, and stunning. On the north face of the mountain lies the Fremont Glacier, a huge expanse of ice and snow reaching across to other peaks and the valley below. The only other glaciers I’ve witnessed up close are on Mt. Rainier, and both times I’ve been completely arrested by them.

I spent about an hour on the summit chatting with other folks who made the hike, taking photos, and reveling in the unimpeded views. It’s also the place I thought about these phases of life. How sometimes when you’re in a place mentally you just have to follow that feeling. I also felt grateful to be on a trip with friends who supported that, who were willing to watch my pup to give me an opportunity to summit, and also weren’t afraid to choose their own experience.

Back at camp, even in the afterglow of a summit and another bucket list sunset at Island Lake, I still struggled with the phase I was in. There was, and is, a part of me that just wants to relax and take it all in. I wrote about it before falling asleep that night:

”I’m glad I climbed Fremont but I often think about wishing I had the time/energy when camping/backpacking to read and journal more instead of when I’m exhausted in my tent at night – like now.

I have this drive to go do and see and struggle to let myself relax or be OK not doing something on these trips. It would be nice to simply read and write my ass off on one of these.“

Leaving the basin was bittersweet, the journey out relaxing and uneventful. The post-trip meal and beer as satisfying as it always is. The Wind Rivers took me by storm and won’t leave my mind any time soon. Fremont stands prominent in my photos and in my mind.

At the end of the day, I am glad I went for the summit. Phases will be phases, and there is joy in letting yourself get carried away in your desires and seeing where they take you. Just like books or films, trips seem to meet you where you are. They morph, or you morph them, to what you need. This trip I needed to go for it. Next time I visit maybe I’ll be in a different phase, and I can simply greet Fremont like an old friend and rest under its watchful gaze, content to simply be.

Photos with me in them are by Nate Dodge and Josiah Walker. Two good fellas to backpack with.